The Congleton Charters

There are preserved in the strong room in Congleton Town Hall some 121 charters and assorted documents. Eighty-one were written before 1500. Ten or so relate to various places in North Wales (Hawarden), Staffordshire (King’s Bromley, Longsdon, Lichfield), and Cheshire (Chester, Hough, Macclesfield, Old Rode, Rope, Stapley, Upton, Wickmalban, Wightreston, Willaston), but most are concerned with properties in Congleton itself.

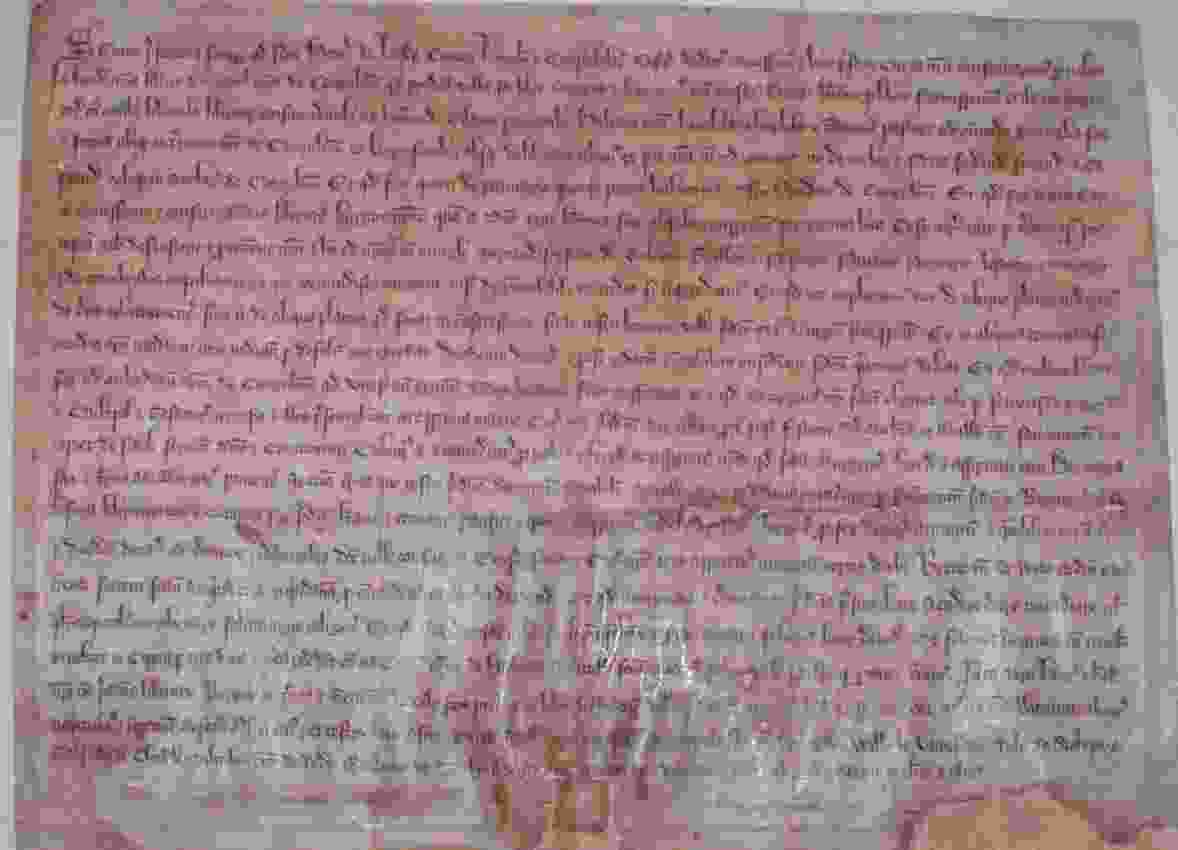

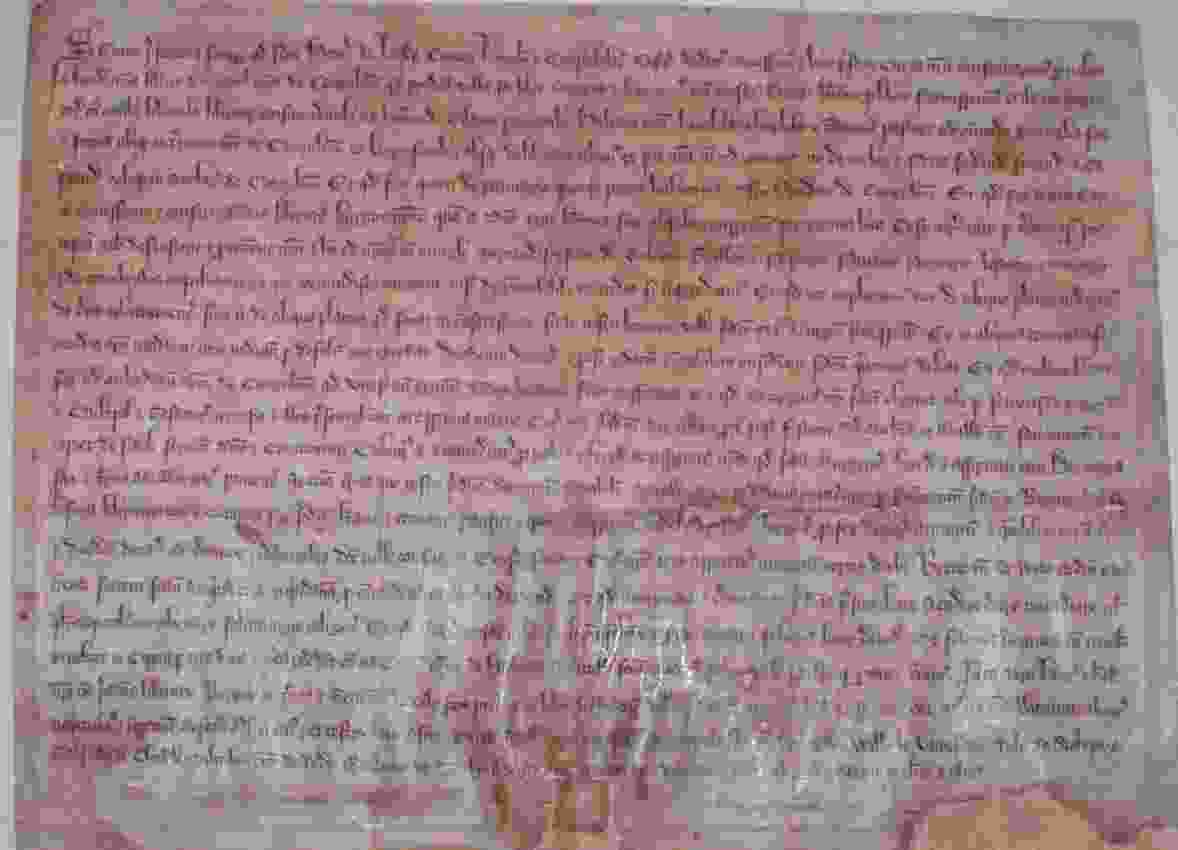

Although for convenience I have characterized the collection as ‘charters’, in reality there are a number of different types of document. The oldest firmly dated item of c.1272 is a charter of Henry de Lacy granting the men of Congleton burgage tenure (the holding of their land by a money rent rather than by personal service) and the right to elect a mayor. There are several other documents outlining the privileges of the lord and his burgesses of various dates as well as a return to Quo Warranto proceedings touching the liberties of the lord of Halton in the early fourteenth century. There are simple charters granting land, numerous chirographs and indentures (both, broadly, agreements of one kind or another), two wills, and Letters Patent granting the right to build a mill after the floods of 1451. Finally, there are miscellaneous items like plans for the construction of a gallery in the upper chapel of the early eighteenth century and a mortgage of the nineteenth.

The collection is what is left of the borough of Congleton’s muniments. A fire destroyed many of its records, but what survived were mounted and restored by the Bodley Library in Oxford and, interleaved with a translation by the Rev. Jonathan Wilson, the school master of Congleton, bound in three volumes. A fourth volume containing four Congleton charters of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was given to the town by James Bradwell in the late nineteenth century.

By 1272 Congleton was probably already an urban community of long standing. Its origins as a trading centre are to be found in the now depopulated village of Davenport some five miles west of Congleton. Davenport means ‘the market on the Dane’ and the place was clearly of some considerable importance before the Conquest, for, according to Simeon of Durham, it was sacked by the Vikings in the early tenth century. By the time of the Domesday inquest (1086) it does not appear to have been distinguished in any way form the surrounding villages. Equally, Congleton was to all appearances no more urban. Significantly, however, both settlements had been held by a certain Godwin in 1066, and, as I have argued elsewhere, it is possible that Davenport’s market functions had already begun to shift to Congleton by then.

The charter of 1272 probably did little more than formalize an existing reality. It was, however, formulated with an eye to maximizing the lord’s profit. Henry de Lacy kept a firm control over the nascent borough community. He retained leet jurisdiction (the maintenance of law and order) in Congleton in the three annual ‘great courts’, a source of considerable profit, as well as the issues of the fairs, market, and the town corn mill. The newly elected mayor was granted what had probably been the three-weekly manorial court with the assizes of bread and ale (the regulation and licensing of baking and brewing) and possibly some of the manorial waste such as the Town Wood and the Byflattes. In return the burgess community assumed responsibility for the upkeep of the Upper Chapel of Congleton, the present St Peter’s Church, the Lower Chapel, across the Dane and now lost, and the town bridge. Much of the documentation is concerned with communal properties acquired by the mayor and burgesses to underwrite these onerous duties.

The collection is a rich source for the history of Congleton, but it is not an easy corpus to use. It would be nice to say that we could match documents to existing properties plots, but, so far, we cannot. Detail is sometimes fulsome. In 1655 there is a fine description of a property:

being of the inheritance of the said William Rode situate and being near to the High Crosse in Congleton, wherein Thomas Burgess of Congleton webster doth now inhabit, containing those parcells of buildings etc hereafter mentioned, that is to say the antient dwelling house with the chamber over the same, and the buttery standing on the back part thereof, the entry or lower flower, the chamber over the same; and also two bayes of the barn standing next the house and the waste ground at the nearer end thereof together with the moytie and one halfe of the yard, orchard, and garden as it is now meered out and divided

But where was it situated in the town? It is impossible to say from the available information. There are references to places that can be located today. Cockshoots makes an early appearance, as do many street names, and some properties are described in relation to features like the bridge and the chapels. But usually descriptions are laconic to say the least.

If the charters are viewed as individual items, this is an insuperable problem. In reality, however, they constitute an archive and the interpretative possibilities of the collection are therefore the greater. The 121 documents do not relate to 121 different properties, but 121 transactions relating to a much smaller number (as yet to be determined) properties. Where details of ownership, tenure, and the like indicate that the same tenement is referred to in a number of charters, then the detail of one can illuminate the others. Thus, a charter of 1445 is on its own seemingly unhelpful:

Charter by which Sir Lawrence Fitton, knight, gives and concedes to Philip Grene mercer of Congulton and to Henry del Broke of Somerforde, two parts of one burgage with the buildings on it, lying in Congulton between a parcel of one burgage on the one part of Randle Maynewaryng and the tenement of John Spenser of the other part; to have and to hold the said two parts….

But fortunately we can see that it is probably the same property that is described as in High Street in a further deed of 1537. I am hopeful that we shall be able to suggest a more precise location once we examine the borough’s properties in the post-medieval period.

It is early days to draw any firm conclusions from the collection. However, initial analysis of this kind suggests that by about 1400 the town was as big as it was in the early nineteenth century. High Street, Mill Street, and West Street, as well as Lawton Street, were already developed to some degree. There was even a burgage across the bridge on Hartslyppe, a lane somewhere near the present Rood Hill. Burgage tenure is evidenced in all parts of the town, but West Street certainly seems to have been one of the richer areas with a number of references to ‘mansions’.

Such a pattern may have considerable importance for an understanding of the development of Congleton. Hitherto it has been argued that the original focus of the settlement was Swan Bank. To all appearances here indeed was an early nucleus: topographically the triangle of buildings defined by Duke Street, Swan Bank, and Little Street looks like infill of a market place into which the axial routes of Bridge Street, Mill Street, and West Street formerly ran. This feature may well have been the nucleus of the borough. But ‘new’ boroughs of the Congleton type were often planted on sites adjacent to older centres of power. The manor of Congleton was probably situated further to the east, the site of the town hall and St Peter’s Church being possible markers. Was there also a separate settlement close to the bridge? What above all characterizes the settlement pattern of Cheshire is its dispersion. Congleton today consists of an aggregation of lots of villages – Mossley, Hightown, Dane-in-Shaw, West heath, Lower Heath, Buglawton etc. It may have been no different in the past.

The archive also illustrates the character and growth of the town. Some of the local gentry from the surrounding area had property in Congleton, indicating that the town was a market centre in East Cheshire. But most of the people mentioned are inevitably the well-to-do tradesmen, the drapers and mercers who dominated town government. What is remarkable about them is that the same names persist over a great period of time. It was a small, only slowly changing, cabal that dominated the town from the fourteenth into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. One would dearly like to know how this patriciate related to the movers and shakers of Congleton’s industrialization thereafter.

Such problems will only be resolved by further study of the Town Hall archive and related documentation as a whole. Most of the nineteenth-century transcriptions have now been posted. In due course, they will be checked against the original charters to produce a modern and critical edition for all to consult. In a broader context the time is ripe to undertake a survey of the standing buildings of Congleton. It is often said that there are no medieval structures left in the town. But the truth is that we have not really looked. Our historic buildings complement our written records and we should study them both as a complete archive.

I am grateful to Congleton Town Council and John Herod, the town clerk, for access to the Congleton muniments and permission to reproduce images of some of the documents. Thanks are also due to Shirley Williams and the Congleton Historical Society for inviting me to give this lecture.

©David Roffe, May 2002.