3. THE COMPILATION OF THE TEXT

Domesday Book was compiled in less than a year and shows many signs of haste. Additions, alterations, omissions and duplications all abound. But the enterprise was a mammoth task and its completion in the present form was a triumph of Anglo-Norman administration.[1] Little independent evidence of the procedure of the enquiry has survived. Its main purpose is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle sub anno 1085:

.....the king was at Gloucester with his council, and held his court there for five days, and then the archbishops and clerics had a synod for three days. There Maurice was elected bishop of London, and William for Norfolk, and Robert for Cheshire - they were all clerics of the king. After this, the king had much thought and very deep discussion with his council about this country - how it was occupied or with what sort of people. Then he sent his men over all England into every shire and had them find out how many hundred hides there were in the shire, or what land and cattle the king himself had in the country, or what dues he ought to have in twelve months from the shire. Also he had a record made of how much land his archbishops had, and his bishops and his abbots and his earls, and - though I relate it at too great length - what or how much everyone had who was occupying land in England, in land or cattle, and how much money it was worth. so very narrowly did he have it investigated, that there was no single hide nor virgate of land, nor indeed (it is a shame to relate but no shame to him to do) one ox nor one cow nor one pig which was left out, and not put down in his record: and all these records were brought to him afterwards.[2]

According to Robert of Hereford, a second set of commissioners was sent out 'to shires they did not know, where they themselves were unknown, to check their predecessors' surveys and report culprits to the king'.[3] Moreover, something of the procedure and what may be the main articles of the inquest are recorded in a Domesday satellite known as the Inquisitio Eliensis:

Here follows the inquiry concerning lands which the king's barons made according to the oath of the sheriff of the shire and all the barons and their Frenchmen, and of the whole hundred court - the priests, reeves, and six villeins from each village. They inquired what was the manor called; who held it in the time of King Edward; who holds it now; how many hides there are; how many ploughs in demesne and how many belonging to the men; how many villeins; how many cottars; how many slaves; how many free men; how many sokemen; how much woodland; how much meadow; how much pasture; how many mills; how many fisheries; how much has been added to, and taken away from, the estate; what it used to be worth then; what it is worth now, and how much each freeman or sokeman had or has. All this to be recorded thrice: to wit, as it was in the time of King Edward, as it was when King William gave the estate, and as it is now. And it was also noted whether more could be taken from the estate than is now taken.[4]

Beyond these sparse details, however, most of the evidence for the making of Domesday Book is found in the text itself. No one procedure was used throughout the country. The commissioners of each circuit tailored their methods to the conditions of administration and, no doubt, to the sources available, to meet the demands of different types of local government and estate structure.[5] Each area, then, presents its own problems of interpretation.

In the account of Nottinghamshire there are only three passages which cast any light on the process in the shire. Ilbert de Lacy claimed the priest's land in Elston, and a quarter of the village of (East) Stoke, against Bishop Remigius of Lincoln, while the witness of the wapentake to his title to land is recorded in the account of his manor of Cropwell (Butler).[6] Both passages may be later, although foreseen, additions to the relevant entries. Somewhat less comprehensible is the reference to 'the men of the neighbourhood' (patria) who did not known through whom or how Godric held his manor in Kingston (-on-soar).[7] There is no clue as to the standing of this nebulous group. All three references, however, indicate that a public session was involved in the survey and that, as elsewhere in circuit 6, rival claims were apparently resolved independently of, and probably later than, the drafting of the text.[8] Thus, in Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and Huntingdonshire claims to land are occasionally indicated in the breves either by an explicit statement which is frequently, although by no means always, a later addition, or by a marginal 'k', for kalumpnia,'claim'. However, the decisions recorded in the Clamores are not incorporated into the text. Aubrey de Vere, for example, held two manors in Yelling and Hemingford (Hunts) of the king, although it is noted in his breve that before the Conquest they had been held by Ælfric of St. Benedict of Ramsey. In the Huntingdonshire Clamores, however, the jurors declared that Ælfric had held the estates for one life only, and that the abbot of Ramsey had recovered them after his death at the Battle of Hastings and had retained them until disseized by Aubrey.[9] The unlawful tenure of the manors, then, is not clear from the account of them in the body of the text. If the problem was realised - and it probably only became apparent in the course of the survey - it was clearly felt at some early stage that the record of the claim to land, or of de facto tenure, was sufficient for the purposes of the survey, for scant regard was paid to disputed tenure or the inconsistencies, such as the duplication of material, that it introduced into the text.

Beyond this, the breves are silent. To reconstruct the minutiae of procedure and the sources of the Nottinghamshire account, we must look to the form of the Exchequer text and the nature of the information that it contains. It is clear from the account of the genesis of the enquiry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that one of the main purposes of the Domesday Inquest was to record the value of the land which was held by King William's men. It is not surprising, then, that the basic unit of textual organisation was the manor, for it was through the lord's hall that the issues of the estate were collected.[10] Thus, the value which is almost invariably appended to the manorial entry includes all the dues rendered by appurtenant holdings of inland and soke, and thereby expresses the unity of the estate around the hall.[11] Much of the information recorded in Domesday Book is therefore related to assets which contributed to the income of the lord's demesne. Ploughteams, villeins who owed labour services, sokemen who rendered tribute, mills, fisheries, woods, pastures, meadows and much else are all recorded in considerable detail because the lord profited from them directly.[12]

The bias of the Nottinghamshire data in this way is illustrated by the record of churches. Some 82 are recorded in the text, but this total conceals a great number of entries in which only fractions, that is shares of, churches, are noted. The actual number of structures represented in the text is probably nearer 85 or 86.[13] Because of such divisions some foundations cannot be identified, but the occurrence of fractions is in itself significant. It indicates that Domesday churches belonged to individuals and could be divided like any other commodity. The bishop of Lincoln, for example, had a quarter of the church of Clifton and Roger de Bully held a second quarter.[14] The owner of the remaining half is not recorded. An analysis of the entries in which the information is recorded confirms this observation. Some 92% of churches are found in manorial or inland entries where they are enrolled, along with meadow and pasture, as part of the manorial stock. The church of the Nottinghamshire Domesday is, as elsewhere, a predominantly private and manorial institution.[15] Domesday Book is therefore a poor guide to ecclesiastical provision in the county.[16] Thus, Southwell Minster, one church we know was in existence before the Conquest, does not appear in the text in the account of the archbishop of York's estates.[17] Elsewhere a similar pattern is found. In Lincolnshire, for example, the existence of a monastery at Winghale and a church at (Long) Sutton is only incidentally noticed in the Clamores.[18] Neither appears in the body of the survey because they did not belong to any particular estate held by a tenant-in-chief of the king. Domesday Book, then, is less likely to record major religious institutions, like collegiate churches, and dependent chapels because they did not contribute directly to the income of a lord's demesne and were consequently of little interest to the commissioners. A similar seigneurial bias is evident in every category of information throughout the survey and counsels great care in the use of its data.

The detailed knowledge of estates that the ordinary Domesday entry implies was almost certainly beyond the competence of a local jury. It is unlikely, for example, that any panel of doomsmen could accurately describe the structure and assessment of the archbishop's manor of Sutton which extended into thirteen vills in two wapentakes.[19] The tenant-in-chief, or his agent, must have provided this type of information.[20] Much else of the manorial data is of this privileged nature. The minutiae of manorial stock and the issues that it produced, can only have been given to the commissioners by manorial officials. Moreover, it is improbable that such essentially unverifiable material was presented in open court sessions. As Galbraith has argued, these matters must have been delegated to 'backroom' sessions.[21] It is clear, then, that the tenant-in-chief made some kind of return. The form of such a source can occasionally be detected. Thus, for example, the description of the archbishop of York's Nottinghamshire fief is divided into three distinct groups (figure 3). The first relates to the land of St. Mary of Southwell in 1066 and the second to that of the archbishop. The third consists of a manor in the wapentake of Lythe which also belonged to Southwell. It seems probable, however, that it is merely an accident that this estate was not included in the first group for, if the normal procedure of the enquiry had been followed, it would have been enrolled at the head of the breve. Estates in the wapentake of Lythe are usually described before those in Thurgarton in which Southwell was situated.[22] But it was clearly displaced by the superior status of Southwell as the caput of the fee, and was therefore relegated to the end of the breve.[23] The account of the land of the archbishop, then, is divided into sections which relate to the interest of the ancient archiepiscopal church of Southwell, on the one hand, and the primate, on the other. The division of the breve in this way is thus related to estate management and is therefore unlikely to have arisen in the compilation of the text from official sources. It can only have been derived from the information that the archbishop provided. The same type of textual arrangement is also found in the returns of the abbey of Peterborough in the Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire folios.[24]

Figure 3: groups of manors in breve no.

5.

A. SOUTHWELL

|

5,1. Southwell 5,3. Cropwell |

B. ARCHBISHOP

|

5,4. Laneham 5,5. S. Muskham (postscriptal) 5,6. Rolleston (postscriptal) 5,7. Sutton 5,9. Blidworth 5,11. Oxton |

C. SOUTHWELL

|

5,13. Norwell |

Although the major source of information, the seigneurial returns were nevertheless not enrolled in the precise form in which they were presented to the Domesday commissioners, but were rearranged in an order of wapentakes which is common to all the breves. Thus, even though the groups of the archbishop's return are preserved in the text, the manors in each are described in the order of the common sequence.[25] It is best illustrated in Roger de Bully's breve for he held land in all eight of the Nottinghamshire wapentakes.[26] The order in which his manors are described is set out in figure 4. Exactly the same sequence is found in the other fiefs once corrections and later additions have been identified. The estates of Count Alan, for example, appear in the order of wapentakes nos. 1, 1, 3, 5, 7, 7, 8.[27] He did not hold land in Bassetlaw, Thurgarton and Broxtow, 2, 4, and 6, so these wapentakes are not represented. Irregularities do occur, especially at the end of breves. The phenomenon probably indicates the accidental omission of an entry and its subsequent enrolment in the only space available.[28] More interestingly, the sequence is sometimes repeated. Once postscriptal material is identified, it is clear that such is the case in each of the three sections of breve no. 5. The same pattern is found in no. 30. In other counties all sorts of permutations occur, but in Nottinghamshire the sequence is generally very regular.[29]

Figure 4: wapentake sequence.

|

|

ENTRY NOS. |

WAPENTAKE |

|

1. |

1 - 5 |

Newark |

|

2. |

6 - 58 |

Bassetlaw |

|

3. |

59 - 71 |

Lythe |

|

4. |

72 - 76 |

Thurgarton |

|

5. |

77 - 89 |

Rushcliffe |

|

6. |

90 - 94 |

Broxtow |

|

7. |

95 - 111 |

Bingham |

|

8. |

112 - 132 |

Oswaldbeck |

It has been suggested that such regular sequences of wapentakes, and in hidated England, hundreds, are a product of the collection of data wapentake by wapentake in open court sessions. For each area of local government, it is argued, a separate quire or pamphlet was used to record the information collected from local juries. The subsequent shuffling of these quires in the course of compilation of the tenurially arranged text gave rise to the various eccentricities of order that are sometimes observable.[30] In circuit 6 this conclusion is implausible for such a procedure would naturally result in the enrolment of parcels of inland and sokeland geographically. In fact, they are usually grouped with the manorial caput, regardless of the wapentake in which they were situated.[31] Soke of Ralf son of Hubert's manor of Barton in the wapentake of Rushcliffe, for example, was enrolled with the caput before his other Rushcliffe estates, even though it was situated in Broxtow.[32] It is more likely that the Domesday scribe, or more correctly the scribe of his exemplar, worked from two sources, one seigneurial, based upon the tenant-in-chief's return which outlined the structure of each manor, and the other geographical, probably based upon taxation records.[33] Such a method would explain the otherwise baffling phenomenon of parallel entries. In the Nottinghamshire folios, as elsewhere, duplication of information is widespread and is usually associated with disputed title or common interests in the same estate.[34] Wulfsi's land in Sutton (Passeys), for example, is enrolled in both William Peverel's breve and the land of the thanes.[35] Count Alan had seven bovates and one fifth of a further bovate in Leverton, half of which, described as three and a half bovates and one half of a fifth bovate, appears in Roger de Bully's breve no. 9.[36] Soke of Southwell in Fiskerton, Morton, Gibsmere, Farnsfield, Kirklington, and Normanton (by Southwell), which was held by tenants-in-chief other than the archbishop of York, is probably included in the assessment of the archiepiscopal manor of Southwell at 22 carucates and 4 bovates.[37] Farnsfield, indeed, is further duplicated in the king's breve.[38] Many such duplications occur [39]and no doubt others remain undetected. But it is evident that the same parcel of land could not repeatedly be entered into separate breves in this way in an open court session. As we have seen,[40] however, de facto tenure, or claim to title, was deemed sufficient in the initial stages of the enquiry and it therefore seems likely that the Domesday scribe accepted the claim of the tenant-in-chief on the basis of his return in the knowledge that disputed title would be resolved at a later date. The same parcel of land was thus enrolled in a number of breves when two or more tenants-in-chief made a claim to it in their returns.

The content of breves, then, was largely determined by seigneurial returns, but their form was derived from a geographically arranged source. In Lincolnshire this source was probably a geld list. The basic unit of local government in the county was not the vill as it is known in the later Middle Ages, but a twelve-carucate hundred. In origin the institution was very artificial. It was derived from a system of taxation based upon a more or less arbitrary quota of carucates imposed upon the shire from above. The area of the hundred therefore varied from wapentake to wapentake according to the rate of carucation. It soon established itself, however, as a territorially-based organisation which was responsible for the functions normally associated with the vill. It is not surprising, then, that it was involved in the Domesday enquiry: the verdict of the hundred is recorded in several places. But its role as a unit of administration had a far more profound affect upon the survey. The seigneurial data were checked, and thereby formulated, by reference to its area. The Domesday entry, then, describes the land of a tenant-in-chief in a hundred. When an estate extended into a number of hundreds, it was therefore naturally described in a number of entries, and the type of entry was determined by the character of the land. Where there was a hall, it was enrolled as a manorial entry and soke in the same hundred was incorporated in the same as 'intra-manorial soke'. Where there was demesne but no hall, the land was described as a berewick. Finally, where there was no demesne, the land appears as soke. Certain types of estate, like the large soke, did not always conform to this pattern. Moreover, parcels of soke which had a distinctive identity were enrolled separately. But a hundredal structure provides the form of most of the text and clearly the scribe had a document so arranged before him.[41]

Vestiges of one such source survive in the Lincolnshire folios. Geoffrey de la Guerche held the whole of the Isle of Axholme which adjoins the wapentake of Oswaldbeck to the north-east of Nottinghamshire.[42] For whatever reason, he does not seem to have returned a detailed account of his fief in terms of the structure of its constituent estates, or the information was not used in the compilation of his breve, for the whole is hundredally arranged: the hundreds can be reconstructed by adding up the assessment of successive entries (figure 5). The only irregularity is entry no. 14; it is a later addition to the foot of the column and presumably duplicates a carucate described elsewhere for it cannot be traced in the Lindsey Survey of c.1115.[43] A further six carucates in Luddington and Garthorpe are duplicated at the end of the breve where the two settlement nuclei of Marshes and Winterton are identified as part of the estates.[44] Berewicks and soke, where the relationship is specified, are always in different hundreds to the manorial caput and no attempt has been made to group them. It evident that this form cannot have been derived from a seigneurial return. A tenant-in-chief would naturally describe his estates in terms of their management. Rather, the precision of the geld assessments, all of which are those of 1066, and the regular geographical order of the hundreds - they proceed from south to north - suggest that the ultimate source is a document concerned with assessment to the geld which recorded the pre-Conquest holder of land and its assessment in every hundred. Reference is indeed made to one such document in circuit 6. A note is appended to the account of the borough of Huntingdon stating that the villeins and sokemen in Hurstingstone Hundred paid geld 'according to the hides written in the record (in breve)'.[45]

Figure 5: DB estates

in the Isle of Axholme.

|

REF |

VILL |

ASSESSMENT |

STATUS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

car. |

bov. |

|

|

|

|

63,5 |

Epworth |

8 |

0 |

manor |

|

|

|

63,6 |

Owston |

4 |

0 |

manor |

|

12 car |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

63,7 |

Haxey |

3 |

0 |

manor |

|

|

|

63,8 |

Eastlound |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Graizelound |

1 |

6 |

two manors |

|

|

|

63,9 |

Ibidem |

1 |

1 |

soke of Epworth |

|

|

|

63,10 |

Ibidem |

0 |

1 |

berewick of Belton |

|

|

|

63,11 |

The Burnhams |

6 |

0 |

soke of Belton |

|

12 car. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

63,12 |

Belton |

5 |

0 |

manor |

|

|

|

63,13 |

Beltoft |

1 |

0 |

soke, unspecified |

|

|

|

63,14 |

Althorpe |

1 |

0 |

soke, addition |

|

|

|

63,15 |

Crowle |

5 |

7 |

manor |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

inland of Upperthorpe |

|

13 car. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

63,16 |

Amcotts |

2 |

0 |

soke of Crowle |

|

|

|

63,17 |

Ibidem |

0 |

3 |

inland of Westwood |

|

|

|

63,18 |

Ibidem |

0 |

5 |

soke of Garthorpe |

|

|

|

63,19 |

Garthorpe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luddington |

4 |

4 |

soke of Crowle |

|

|

|

63,20 |

Ibidem |

1 |

0 |

manor |

|

|

|

63,21 |

Ibidem |

0 |

4 |

soke of Belton |

|

|

|

63,22 |

Butterwick |

3 |

0 |

soke and inland of Owston |

|

12 car |

Exactly the same type of hundredally-arranged geld list probably gave form to the Nottinghamshire Domesday. The decisive evidence is found in the Domesday account of Roteland which was an integral part of the administration of the county in 1086. The links between the two are almost certainly as early as carucation for the two hundreds of Alstoe were accounted in the quotas of the wapentakes of Thurgarton and Broxtow.[46] The procedural processes that the Roteland text reveals, and the local government that it implies, is therefore of great relevance to an understanding of the administrative structure of Nottinghamshire. Like the account of the wapentake of Axholme, the Roteland text is hundredally arranged (figure 6). It commences with a statement of the assessment of the area: the wapentake of Alstoe was rated at two hundreds, each of twelve carucates, and Martinsley at one hundred. From the entries that follow, the two hundreds of Alstoe, both territorially discrete, can be reconstructed by adding up consecutive entries.[47] The assessment of Martinsley is thirteen carucates. But the four carucates of the king's manor of Oakham almost certainly include the carucate at which the dependent manor held by Fulchere Malsor was assessed,[48] thereby reducing the total to twelve carucates. Uniquely in Domesday Book, no attempt has been made to group the estates of each tenant-in-chief. Countess Judith held lands in both hundreds of Alstoe, but the description of her manors is separated by that of the fees of Alfred of Lincoln and Robert Malet, and the king held manors in the north hundred (no.1) and in Martinsley which are enrolled at the beginning and the end of the whole account. The form of the text is completely hundredal for no interest was taken in settlement or estate structure per se. Thus, Robert Malet's manor was originally identified simply by 'In the same hundred', that is, the northern hundred of Alstoe. Only later was the place-name 'Teigh' interlined to identify its actual nucleus. Moreover, again originally, there was no mention of dependent holdings. Only subsequently have the number of berewicks of Oakham, Ridlington and Hambleton been added. It is clear, then, that the form of the account of Roteland was ultimately derived from a geld list and, indeed, the record of wapentake geld quotas is almost certainly taken directly from such a source.

Figure 6: the Roteland Domesday.

|

HUNDRED |

MANOR |

LORD IN 1086 |

ASSESSMENT |

|

|

|

|

Alstoe I |

Greetham |

King |

3 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Cottesmore |

King |

3 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Mk Overton Stretton |

Countess Judith |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

Thistleton |

Countess Judith |

0 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

Ibidem |

Alfred of Lincoln |

0 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

Same hundred (Teigh) |

Robert Malet |

1 |

4 |

12 car. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alstoe II |

Whissendine |

Countess Judith |

4 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Exton |

Countess Judith |

2 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Whitwell |

Countess Judith |

1 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Awsthorp |

Oger son of Ungomar |

1 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Burley |

Gilbert de Gant |

2 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Ashwell |

Earl Hugh |

2 |

0 |

12 car |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Martinsley |

Oakham |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(5 berewicks) |

King |

4 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Ibidem |

Fulchere Malsor |

1 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Hambleton |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(7 berewicks) |

King |

4 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Ridlington |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(7 berewicks) |

King |

4 |

0 |

13 car. |

|

|

Words in brackets are interlineations. |

|

|||||

As it stands, then, the Roteland Domesday originated as a geographically arranged source into which the description of estates, no doubt substantially derived from seigneurial returns, has been inserted. As such, it appears to be a type of document similar to the Inquisitio Comitatus Cantabrigiensis, that is a vill-based account of a county produced in the process of compilation of the final seigneurially-arranged text of the 'original returns' and the Exchequer Domesday.[49] This impression, however, is probably erroneous. The relationship between the Roteland Domesday and the more usual form of the survey can be directly observed. Eight out of twelve of the Alstoe entries are duplicated in the Lincolnshire text where, occupying their own position in the wapentake sequence, they are enrolled in the breves of the tenants-in-chief in the normal way.[50] Nevertheless, there is no direct relationship between the two versions for each contains details which are not found in the other. Alfred of Lincoln's tenant in Thistleton, for example, is omitted in the Roteland account, but is named as Gleu in the Lincolnshire folios, while Countess Judith's estate in Stretton is identified as a berewick in the one, but its status is unspecified in the other.[51] It seems likely, in fact, that they are two independent compilations for, significantly, the land held by the king is not duplicated in the Lincolnshire text. The Domesday account of terra regis is frequently anomalous and appears to be derived from sources other than those used in the compilation of the body of the text.[52] It is possible, then, that Roteland formed a separate entity in a survey of royal lands and dues which was an early stage in, and an independent element of, the Domesday Inquest. In the subsequent survey of the lands of the tenants-in-chief, however, the data were collected through the administration of the shire of Lincoln and therefore appear in the account of the county. Nevertheless, the form of the two versions is evidently derived from a common source for Countess Judith's manors are described in the same order in each (figure 7). This source is clearly the same hundredally arranged geld list and it is this that is the common datum of the two versions. In enrolling the account of the royal lands in Roteland, it was treated as one estate and no attempt was made to arrange the material in a seigneurial form. It is possible that, just as part of Gilbert de Ghent's land in Empingham, in Witchley Hundred, in Northamptonshire in 1086, was in the king's soke of Roteland, so the crown had reserved regalian dues throughout the two wapentakes of Martinsley and Alstoe.[53]

Figure 7: parallel entries in the Roteland

and Lincs. folios.

|

RUTLAND DB |

LINCS. DB |

|

R7 Mk. Overton |

56/11 Mk. Overton |

|

R8 Thistleton |

56/12 Thistleton |

|

R11 Whissendine |

56/13 Whissendine |

|

R13 Exton |

56/17 Exton |

|

R13 Whitwell |

56/18 Whitwell |

Since Roteland was an integral element in the administrative machinery of geld collection in Nottinghamshire, it might be expected that the same structures existed in the county and gave form to the Domesday account in the same way. There is evidence to suggest that such was indeed the case. Three hundreds - Southwell, Blidworth and Plumtree - are incidentally named in the Nottinghamshire text.[54] Their assessment is nowhere given, but there is no reason to doubt that it was twelve carucates, or that the institution was identical with that found in Roteland. The larger hundreds of carucated Leicestershire and the East Riding of Yorkshire cannot be intended because of the low rate of carucation in the shire.[55] Moreover, as elsewhere, the system was probably general.[56] A note is appended to the description of Gilbert Tison's manor of Averham stating that five sokemen were attached to the manor 'in other hundreds'.[57] This reference tends to suggest that the institution was taken for granted and was therefore only mentioned in exceptional circumstances. Indeed, all three of the named hundreds appear in unusual contexts. In Farnsfield Walter de Aincurt had two bovates of land; one was soke of Southwell, the other belonged to the king, but it nevertheless pertained to the hundred of Southwell.[58] As in Lincolnshire, it would appear that the land of the king did not normally belong to a hundred.[59] Thus, it was probably felt necessary to record an exception. The notice of Blidworth occurs in a postscriptal rubric which may refer to the entry identified as Alwoldestorp for it is appended to the last line of the description of Gilbert Tison's manor in the same place.[60] However, rubrics in such a position normally refer to the following entry, and therefore the reference is more likely to be to Staythorpe. Thus, the fact was probably recorded because the parcel of land was remote from the body of the hundred.[61] The third is mentioned in the account of Henry de Ferrers' manor of Leake. There was a berewick of the estate in the same place, but it was situated in Plumtree Hundred.[62] This implies that the manorial caput belonged to another unit of local government. Plumtree, therefore, was probably noticed because the settlement of Leake was divided between two administrative districts. The lack of references to the hundred is not unusual. The Domesday Inquest was not a survey of local government. It was a record of resources held by the king and his men. There was no pressing reason, then, to identify areas of public administration.[63]

Unfortunately, it has not proved possible to reconstruct any of the three named hundreds. That of Southwell is subsumed in the compound entry for the Southwell estate. A reconstruction of Blidworth has recently been suggested, but the result is unsatisfactory, although substantially plausible, not the least because the total is eleven rather than twelve carucates.[64] Plumtree likewise appears to be an insoluble problem. The low assessment of Nottinghamshire and the inaccuracies in the record of geld in Domesday Book made the task exceedingly difficult.[65] However, two hundreds can be identified in the wapentake of Broxtow through a peculiarity in the record of assessment. In the Nottingham-shire Domesday teamlands almost invariably exceed geld carucates. But to the north and west of Nottingham there is a group of vills in which the figures are identical in every entry (figure 8). In Nuthall, for example, there were two holdings of four and a half and three and a half bovates in which there was land for four and a half and three and a half oxen respectively.[66] The area so defined includes only part of Bas-ford, Newthorpe and Watnall, and has a total assessment of 34 carucates and 6 bovates. Ten carucates and six bovates, however, belonged to the king and must therefore be subtracted from this total since terra regis was not incorporated into the hundredal system.[67] There remain two self-defined, geographically discrete, groups of entries, here identified as A and B, assessed at exactly twelve carucates each.

Figure 8: two hundreds

in the wapentake of Broxtow.

|

HUNDRED A |

HUNDRED

B |

|||||||

|

REF. |

VILL |

c. b. |

t. o. |

REF. |

VILL |

c. b. |

t. o. |

|

|

10,63 |

Newthorpe |

0 2 |

0 2 |

10,66 |

Bulwell |

2 0 |

2 0 |

|

|

10,43 |

Watnall |

1 0 |

1 0 |

1,45 |

Arnold |

3 0 |

3 0 |

|

|

10,47 |

Kimberley |

1 0 |

1 0 |

10.51 |

Basford |

2 3 |

2 3 |

|

|

10,40 |

Nuthall |

0 4½ |

0 4½ |

10.52 |

Basford |

0 1 |

|

|

|

30,32 |

Nuthall |

0 3½ |

0 3½ |

30,34 |

Basford |

0 4 |

0 4 |

|

|

10,36 |

Cossall |

0 6 |

0 6 |

10,15 |

Radford |

3 0 |

3 0 |

|

|

13,12 |

Cossall |

0 6 |

0 6 |

1,48 |

Lenton |

0 4 |

|

|

|

10,27 |

Strelley |

0 6 |

0 6 |

10,19 |

Lenton |

2 0 |

2 0 |

|

|

10,28 |

Strelley |

0 3 |

|

10,24 |

Lenton |

0 4 |

0 4 |

|

|

30,31 |

Strelley |

0 3 |

0 3 |

10,17 |

Morton |

1 4 |

1 4 |

|

|

1,50 |

Bilborough |

0 1 |

|

B1 |

Nottingham |

6 0 |

|

|

|

10,39 |

Bilborough |

0 7 |

0 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,49 |

Broxtow |

0 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28,3 |

Broxtow |

0 3 |

0 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

29,2 |

Trowell |

1 4 |

1 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30,30 |

Trowell |

0 4 |

0 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30,50 |

Trowell |

0 4 |

0 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30,51 |

Trowell |

0 4 |

0 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,47 |

Wollaton |

1 0 |

1 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,35 |

Wollaton |

1 4 |

1 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

13 2 |

|

|

|

21 4 |

|

|

|

King's

land

|

1 2 |

|

|

|

9 4 |

|

|

|

TOTAL GELDABLE

|

12 0 |

|

|

|

12 0 |

|

|

|

|

NB: assessments of royal estates are italicised; c = carucate, b = bovate, t = teams, o = oxen. |

||||||||

:

These two units are almost certainly twelve-carucate hundreds. They are considerably larger than those of Lincolnshire, but are comparable with those found in Roteland and Derbyshire.[68] Moreover, their area had a demonstrable affect upon the form of the text. The relationship is illustrated by the six entries in which land in Basford is described. The vill is assessed at four carucates and four bovates, but three carucates belong to area B (figure 8) and the remainder to the land to the north where teamlands exceed carucates to the geld. The account of the six entries identified as Basford appears in two breves (figures 2 and 9). In no. 10 William Peverel held a manor in Basford in succession to Alwin. Land of Aswulf is entered next, although marked for deletion. But some 27 entries later it is found appended to two further manors in the same vill which had belonged to Alfheah and Algot.[69] In breve no. 30 a similar pattern is evident. In 1066 Aelfric held two manors in Basford which were waste at the time of the survey. A postscriptal addition to the text records that Aswulf had held a further bovate which was also waste. Six entries later presumably the same Aelfric is recorded as holding four bovates in the same vill which he had also held in 1066.[70] In both breves, then, the account of Basford is divided into two distinct sections. In the one, entries are enrolled in which teamlands exceed carucates to the geld, in the other, entries in which the assessments are equal. The division is clearly a significant one for land of apparently the same individual is somewhat artificially divided between the two. The dichotomy evidently relates to different units of local government and, since area B, in which the second group of Basford entries is situated, is assessed at twelve carucates, it can be confidently identified as a hundred. It is clear, then, that a hundredal structure lies behind the text in these two breves.

Figure 9: entries

relating to Basford in breve no. 30.

|

REF. |

VILL |

STATUS |

TRE TENANT |

TRW TENANT |

|

30,28 |

Basford |

two manors |

Aelfric [Aswulf] |

waste |

|

30,29 |

Papplewick |

unspecified |

Aelfric, |

Alfsi, |

|

|

|

|

Alric |

waste |

|

30,30 |

Trowell |

manor |

Ulfkell |

Haldane |

|

30,31 |

Strelley |

manor |

Ulfkell |

Wulfsi Godwin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30,32 |

Nuthall |

manor |

Askell |

Aelfric |

|

30,33 |

Awsthorpe |

manor |

Ulfketel |

Haldane |

|

30,34 |

Basford |

manor |

Aelfric |

Aelfric |

|

NB: words in square brackets [ ] have been interlined |

||||

. Comparable evidence is not available for the rest of the Nottinghamshire folios. However, the regularity of villar sequence, common to all breves, is suggestive. It will be noticed that, with minor irregularities in breve no. 10, the vills of each of the hundreds identified in Broxtow Wapentake are grouped together in the same order in the text wherever they appear. The same pattern is found elsewhere. In Oswaldbeck Wapentake, for example, the vills are described in the same order, with two minor exceptions, in breves nos 1, 5 and 9. A second list in no. 5 is inverted (figure 10). The appearance of Bole in two separate contexts may indeed imply that the settlement, like Basford, was divided between two hundreds. As late as 1315 it was situated in two vills.[71] Compound entries in breve no. 5 have, however, precluded any attempt to reconstruct the hundreds of the wapentake.[72] But the phenomenon is consistent with the pattern observed in the wapentake of Broxtow. It can be concluded, then, that a hundredal structure is probably present in the whole of the Nottingham-shire Domesday.

Figure 10: Oswaldbeck

Wapentake: villar sequence.

|

BREVE NO. 1 |

BREVE NO. 5 |

BREVE NO. 5 |

BREVE NO. 9 |

|

31 Tiln |

|

8a Tiln |

|

|

32 Leverton |

4g Leverton |

|

|

|

33 Fenton |

|

|

112 Fenton |

|

34 Littleborough |

|

|

|

|

35 Sturton |

|

|

114 Sturton |

|

36 Wheatley |

4f Wheatley |

|

115 Wheatley |

|

|

4e Burton |

|

116 Burton |

|

|

4d Bole |

|

117 Bole |

|

|

4b Beckingham |

|

118 Beckingham |

|

37 Walkeringham |

|

|

120 Walkeringham |

|

38 Misterton |

|

|

121 Misterton |

|

|

|

|

122 Gringley |

|

|

|

|

123 Bole |

|

39 Wiseton |

|

|

|

|

40 Clayworth |

|

|

126 Clayworth |

|

41 Clarborough |

|

|

127 Clarborough |

|

and Tiln |

|

|

|

|

42 Welham and |

|

8b Welham and |

|

|

Simentone |

|

Simentone |

|

|

43 Gringley |

|

8c Gringley |

|

|

44 Saundby |

4c Saundby |

|

|

|

|

|

8d Scaftworth |

|

|

|

|

8e Everton |

|

|

|

|

|

129 Treswell |

|

|

|

|

131 Rampton |

|

4a Askham |

|

|

|

It is now possible to understand the method of compilation and some of the characteristics and forms of the Nottinghamshire text. Like the Lincolnshire and Roteland folios, it almost certainly has an underlying hundredal structure which gave form to entries and determined the order in which they appear in each breve. Much of the information which lies behind the descriptions of manors was provided by seigneurial officials. They must have furnished details of not only stocking and population, but also the structure of each estate. Occasionally the form in which their return was made to the commissioners was retained in the text - the arrangement of the archbishop's fief is probably derived from his return and the large number of compound entries in his breve suggests that it was hardly processed at all. This feature is especially typical of large sokes. But more usually the lord's return was checked against a hundredally arranged geld list and land was enrolled by reference to it. Thus, while the overall form of the manor was retained, the composition of each entry was determined by the area of the hundred. In Lincolnshire, and probably in Yorkshire, it varied in extent, but was generally small. Thus, estates tend to be situated in more than one hundred and are therefore described in more than one entry. Needless to say, the resulting 'manors', 'berewicks' and 'sokelands' do not necessarily have analogues in estate structure.[73] In Nottinghamshire a similar process can be identified. We have already seen that the accounts of the estates of Aelfric and Henry de Ferrers in Basford and Leake derive their respective forms from the underlying hundredal structure.[74] But the same process is not always so readily apparent for the hundreds of the county were considerably larger than elsewhere on account of the high rate of carucation in the shire. Estates were more likely, then, to be located in their entirety in a single hundred. It is probably precisely for this reason that there are relatively fewer entries in the Nottinghamshire Domesday, and that a high proportion of them are described as manors. Situated in the same hundred as the lord's hall, what would elsewhere be entered as separate inland or soke is incorporated into the manorial entry. As is clear from the Roteland folio, the Domesday Book commissioners were not interested in settlement, nor indeed in estate structure, as such. It was the hundred which provided their datum. It is apparent, then, that the form of the Nottinghamshire text does not necessarily imply a difference in development or management of estates, much less variations in settlement patterns, from the rest of the Danelaw. The predominance of manors is merely a function of the procedure of the enquiry.

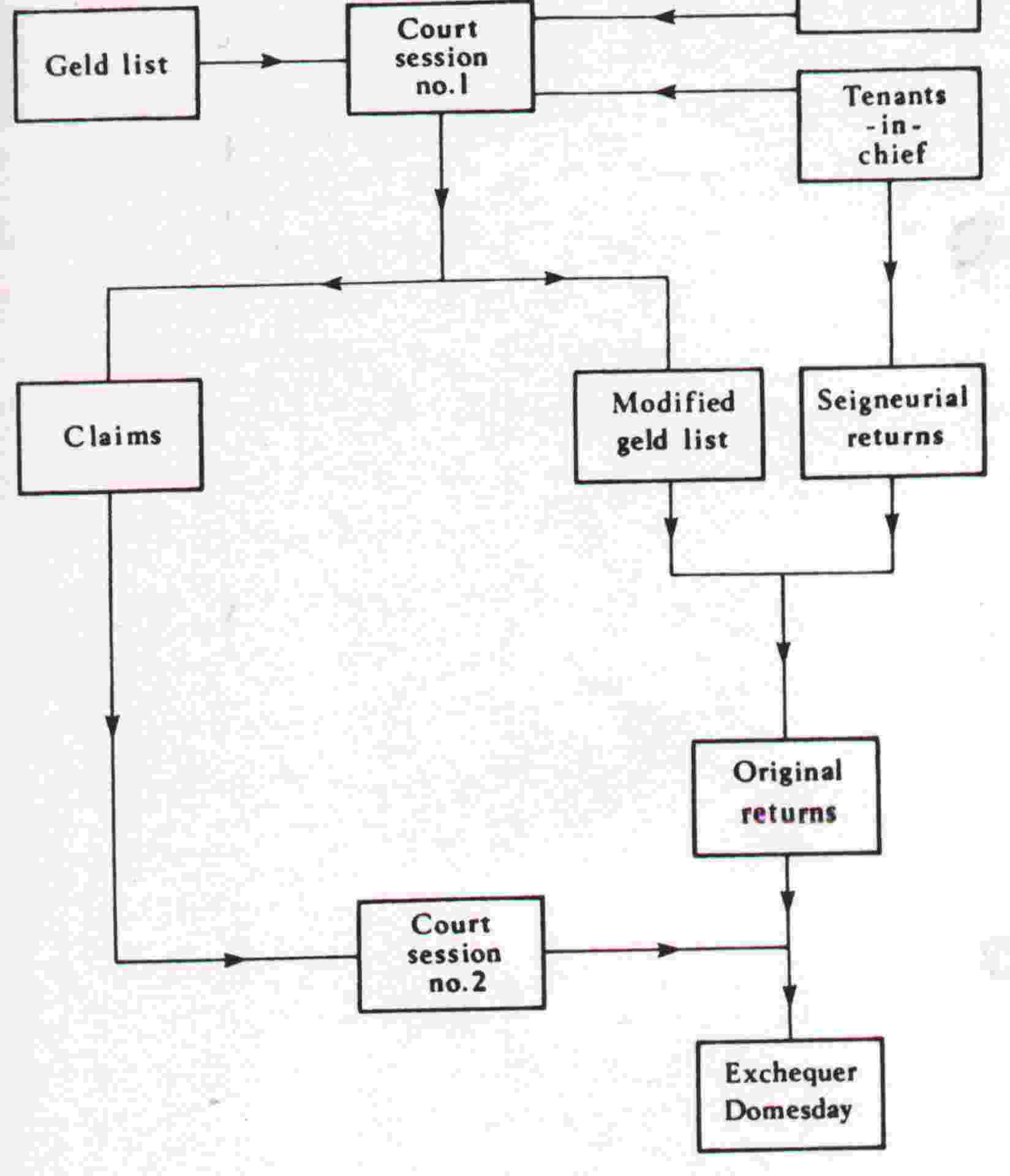

Much of the work of the Inquest, then, was an official procedure which drew upon various types of documents and sources. The role of the county and wapentake courts was probably confined to presentments on title and tenure. As we have seen,[75] the commissioners certainly took evidence from the men of the shire. But it is unlikely that the bulk of the data was collected at this time. The scattered references throughout circuit 6 to the initial session indicate that all the administrative units of the shire were represented - hundred, wapentake, the riding in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, and the shire itself.[76] In Nottinghamshire we only hear of the shire, but 'the neighbourhood' (patria) may refer to a hundred.[77] From what can be perceived of the proceedings, tenure of, and title to, land seem to have been the main concern. Thus, the patria declared that they did not know how or through whom Godric held a manor in Kingston (on-Soar) in succession to Ulfketel.[78] Godric was probably present at the session and could not substantiate his title either by right of his predecessor or of the king's writ. In Derbyshire we hear that Walter de Aincurt cited the king as protector of his land in Brampton and Wadshelf, while Henry de Ferrers called to witness his deliverer in support of his claim.[79] These two references, typical of those few which survive in the text, probably encapsulate in its essentials the whole business of the initial open-court session of the enquiry: it consisted in the collection of evidence. The tenants-in-chief made their claims and the men of the shire made their presentments as to who held in 1086 and, by reference to 1066, by what right. The basic checklist was a geographically arranged geld list recording TRE tenant and assessment to the geld. No doubt a suitably annotated copy was subsequently used in the compilation of the original return or an earlier recension. Matters of fact or uncontentious issues seem to have been accepted without formality. But there is no evidence to suggest that suits were determined at this time. Rival claims were merely noted for resolution at a later stage. Thus, it was apparently in the initial session that Alfwold and his brothers claimed four and a half hides in Huntingdonshire against Eustace the Sheriff. The fact is recorded in Eustace's breve, along with the possibly postscriptal comment that the whole hundred bore testimony in their favour.[80] But this did not settle the matter. It was resolved in a second session which either post-dates, or was independent of, the compilation of the original returns for judgement was given in Alfwold's favour according to the presentment of the county which is recorded separately from the breves in the Clamores.[81] Unfortunately, in circuit 6 the record of these proceedings only survive for Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and Huntingdon-shire. But it is apparent that the resolution of disputes was an important element or consequence of the Domesday Inquest for similar proceedings survive in other circuits.[82] We have no grounds to suspect that Nottinghamshire was different. The shire seems to have been the forum and, unlike the earlier session, the hundred does not seem to have been present for evidence was only taken from the wapentake, riding and shire, and this formed the basis of the judgement. In exceptional cases, however, particularly difficult matters were referred to the king.[83] No concerted attempt was made to correct the breves in the light of such decisions, but postscriptal material suggests that some ad hoc revision was undertaken.

The procedure of the enquiry is represented diagramatically in figure 11.

Figure 11: the

procedure of the Domesday Inquest in circuit 6.